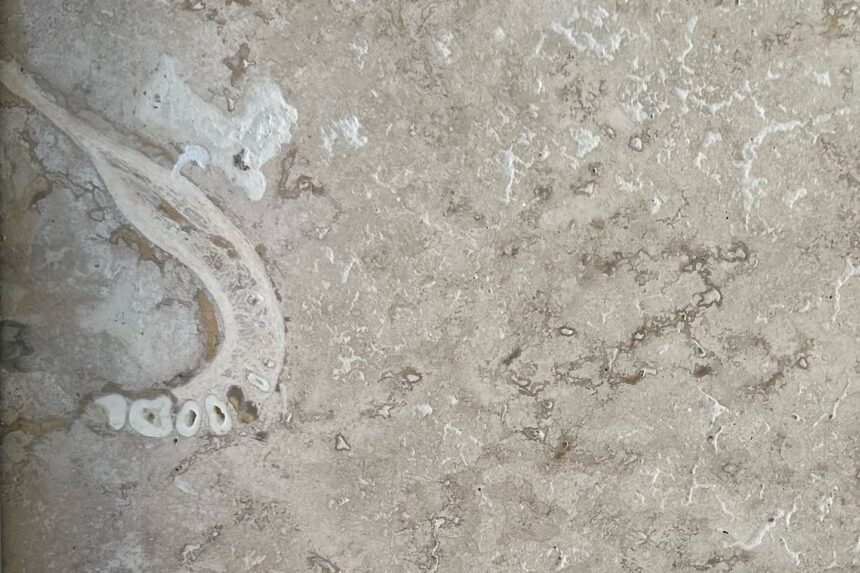

“It’s not so much the teeth that I noticed but the shape of the mandible that is very recognizable,” the dentist, known as Reddit user Kidipadeli75, wrote in an email. He spoke on the condition of anonymity to protect his family’s privacy.

He pointed out that the object in the tile bears a striking similarity to a slice of an image taken with a form of CT scan used in dentistry. “As I am specialized in implant dentistry I work with this kind of image everyday and it looked very familiar,” he said.

The tile, made of a type of limestone called travertine, was imported from a quarry in Turkey. Scientists are now working with the dentist to make sure the tile is properly studied — along with a few other suspicious-looking tiles installed in the house.

While this all may seem quite shocking, paleoanthropologists were both fascinated and a little unsurprised. Travertine can form quickly, but the stones used for commercial purposes tend to come from deposits that have formed over hundreds of thousands of years, ruling out a recent death.

This tile came from a quarry in the Denizli Basin in western Turkey, where the stone has previously been dated to 1.8 million to 0.7 million years ago, according to Mehmet Cihat Alcicek, a professor at Pamukkale University in Turkey who is part of the scientific team that plans to study the mandible.

This viral photo is a reminder that travertine, which forms near hot springs and is valued as an architectural material, often contains old fossils, and that digging it up can unearth ancient treasures. Those fossils can be anything that washes into the spring, from plants, freshwater crabs, deer and reptiles to — on occasion — human remains.

John Hawks, a paleoanthropologist at the University of Wisconsin at Madison, titled his blog post on the matter: “How many bathrooms have Neanderthals in the tile?”

“Every time I am in Home Depot, I go through the travertine tile looking for fossils!” said John W. Kappelman Jr., a paleoanthropologist at the University of Texas at Austin.

Fossils preserved in travertine

Scientists have found a menagerie of ancient fossils embedded in travertine from the Denizli Basin, including remains of mammoths, rhinos, giraffes, horses, deer, reptiles and turtles, according to Alcicek.

Researchers have also found at least one other ancient human in tile. In 2002, Alcicek began studying the formation of travertine in the Denizli Basin. Workers in a tile factory had been cutting stone when they noticed an ancient human fossil, part of a skull. The travertine had been sliced into a slab a little more than an inch thick, so parts of the skull had probably been destroyed — but fragments of the skull cap were recovered.

Alcicek and Kappelman studied the skull fragments, now known as the Kocabas hominin, and found it was the first specimen of Homo erectus to be discovered in Turkey. The skull fragments bore small lesions that were an indicator of tuberculosis, showing evidence of that pathogen in an ancient human. Recent efforts to date the specimen suggest it is more than a million years old.

“Who knows how much of the rest of it from the inferior portion of the cranium on down went unnoticed? We joke that maybe it was a complete skeleton, all the way to the tip of its toes,” Kappelman said in an email. “We literally spent weeks going through the discard pile at the factory looking for any additional bits but no go.”

It’s possible that other parts of the remains went on to be installed in kitchens.

Quarries elsewhere in the world have yielded similar finds. Parts of two hominin skulls and a mandible were discovered during excavations at a quarry in Bilzingsleben, Germany. Hawks said in his blog that they are thought to have been early Neanderthals or a different early human, Homo heidelbergensis.

But how common are incidental finds of ancient human remains in architectural tile?

“It’s twice as common as it was last week!” Hawks said in an email.

Buzz among paleoanthropologists

The latest find created immediate buzz among scientists who study ancient humans. Several paleoanthropologists said it was too tricky to hazard a guess from a photo as to the age or the precise species, but said it was absolutely worth following up on.

“It is clearly a human relative of some kind, but to rule out modern human or find out which ancient population it may belong to will take detailed study,” Hawks said.

Kappelman suggested that follow-up studies could include taking CT scans and 3D-printing the mandible, or perhaps even trying to see if ancient DNA could be recovered. The enamel of the teeth could be scrutinized to learn about what this individual ate.

The dentist who discovered the mandible said that he was inundated with interest from researchers from multiple universities after his Reddit post, and he is working with them now in hopes of learning more about the specimen. He said those researchers have also reached out to the company that sold the travertine to track the batch to the quarry and look for more pieces there.

Hawks said that, in general, if people see what might be human remains in their tile, they should contact local authorities. Laws vary, but in the United States, the process might involve a call to the state archaeologist or historical society.

Alcicek said that after the Homo erectus found in a factory was thoroughly studied, it was given to authorities and is now on exhibit in the Denizli Museum. He expected something similar would happen after the new specimen is carefully examined.

The entire episode is a reminder that construction projects and quarries have what Hawks calls an “uneasy symbiosis” with archaeologists. They can both expose and destroy ancient remains.

“The main constraint on finding the fossils is whether the travertine is being quarried!” Hawks wrote in an email.