Queens prosecutors recently visited a key witness in a wrongful conviction claim filed by a man who has been in prison for 30 years and threatened her with arrest if she changed her original testimony and testified in his favor, court papers filed Tuesday allege.

The witness, Vanessa Thomas, is central to Allen Porter’s claim he was wrongly convicted in the 1991 double killing of a rival drug dealer and his girlfriend. Court papers allege an undisclosed deal prosecutors gave her in 1993 following her own arrest in the crime paved the way for her to falsely implicate Porter.

That allegedly improper arrangement is detailed in Porter’s pending 51-page motion to overturn the conviction, which – supported by the recantations of two other key witnesses and over 2,000 internal case documents – accuses Queens prosecutors and cops of withholding evidence and coercing witnesses in the case.

Thomas, now 70, told her ex-boyfriend, Nathaniel Wright, the two prosecutors came to her home in Georgia on April 4 and said she would be charged with perjury if she changed her original testimony, according to Wright’s April 15 affidavit, filed Tuesday in the case.

Thomas’ trial testimony put Porter at the scene of the murders and claimed he plotted to kill the rival dealer.

Porter’s legal team filed the affidavit along with a 30-page request for a hearing on the matter in Supreme Court in Queens.

“They are entitled to visit her. The fact that threats were made, that’s where it crossed the line and became inappropriate,” said Daniel Barli, Porter’s lawyer. “We believe he’s been wrongfully incarcerated for a crime he didn’t commit and we are taking steps to make sure he gets a fair opportunity to be heard.”

Wright’s affidavit is based on a 390-word text message from Thomas to him sent at 9:17 a.m. one day after the visit from prosecutors.

“Them prosecutors said they are going to do everything in their power to keep (Porter) in prison,” Thomas wrote in the text message.

“Anyone who changes their after 20 years and lie and try and help him, that person is also going to be prosecuted. This ain’t no game.”

“When I spoke to Vanessa about her text, she confirmed to me that she both authored it and sent it to me,” Wright wrote in the affidavit.

Bennett Gershman, an expert on prosecutorial ethics retained by Barli, wrote the hearing is critical to determine if the prosecutors “improperly interfered.”

“Porter’s motion has been tainted by prosecutors threatening Vanessa Thomas to stick to her original and false testimony,” Gershman, a Pace University law professor, wrote.

Richard Brown was the DA when the Porter case was tried. A spokeswoman for the current DA, Melinda Katz, said: “The baseless allegations of threats, as well as any substantive arguments in the motion, will, as always, be addressed in court.”

Daily News / Barry Williams for Daily News

Former Queens DA Richard Brown in 1991 and current Queens DA Melinda Katz in 2023. (Daily News / Barry Williams for Daily News)

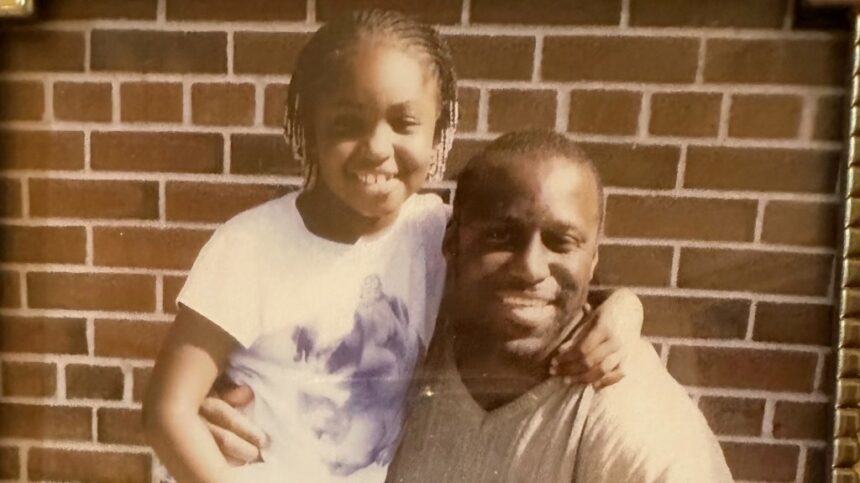

Porter, 51, is serving a 47 years to life sentence in Green Haven Correctional Facility in Stormville. He counsels teens there and is in his second year in the Bard College Prison Initiative.

In 1991, he was 19 and a small-time drug dealer working one side of the Woodside Houses in Astoria for Earnest “Budd” Jarvis. Rival dealers Charles Bland and Mark Rogers sold their product on the other side of the housing project.

Late on Dec. 30, 1991, Bland, 25, and his girlfriend Cherrie Walker, 20, were shot dead in a parking lot in the development on the southwest corner of 51st St. and Broadway. Walker’s 4-year-old son was in the back seat.

The murders rated only a one-paragraph story in the New York Times. What followed is detailed in Porter’s motion filed in November and hundreds of case documents reviewed by The News:

Witnesses described two or three gunmen fleeing in dark clothing, but there was no physical evidence that led to a suspect. Cops focused on Jarvis immediately but he was murdered four weeks later.

Porter was questioned but refused to cooperate out of fear for his family. He was arrested about 90 days later and spent three years in jail awaiting trial.

Thomas’ testimony was central to the case. At trial, she testified she cooperated voluntarily with police and claimed she saw armed men with Porter the night of the murders, and he later told her he had been planning to kill Bland for months.

In his closing argument, prosecutor Richard Schaeffer declared Thomas testified “to relieve herself of the guilt she carries.”

But in 2018, Porter’s legal team unearthed that, in fact, Thomas was arrested in Georgia in November, 1993 and charged with the murders on a warrant from New York. Case records filed with Porter’s motion show the charges were dropped against Thomas only after she agreed to point the finger at Porter.

Prosecutors never told Porter’s defense about this sequence as required under the law, his trial lawyer Edwin Schulman confirmed in an affidavit.

The prosecution also didn’t tell the defense that detectives arrested Wright with Thomas the same day. He was held without seeing a judge for several days before he agreed to implicate Porter to save Thomas from prison.

In July 2021, Wright detailed those events in a handwritten affidavit from a Georgia prison where he was serving a sentence for an unrelated assault case.

“I was terrified because … Vanessa stood to go to prison,” he wrote.

Wright also wrote that when he told detectives the nickname of one of the shooters, a detective corrected him with a full name. He was brought from jail four times to Schaeffer’s office without his lawyer present. And in their first meeting, Schaeffer allegedly told Wright he knew Porter was not the shooter, but Porter had refused to cooperate. Schaeffer could not be reached for comment.

“My only reason for giving this affidavit is because Allen did not commit this crime,” Wright wrote.

A third witness, Jacqueline Aviles, then 17 and pregnant, testified she saw Porter shoot the couple. Schaeffer declared in closing she too had no ulterior motive for coming forward, a transcript shows.

But in October 2021, Aviles gave a lengthy interview to Porter’s legal team recanting her testimony and alleging she had been coerced by two detectives, the motion states. She admitted she couldn’t identify the shooters because they were masked. She said she testified falsely out of fear of losing her children.

Aviles said she had told the detectives several times she saw nothing, but they said they would keep coming at her. One detective slammed his hand on a table and demanded she write a statement.

“The detectives then told her bits and pieces of what to say, and said, ‘You’re not stupid, you can fill in the blanks,’ the motion alleges.

The detective showed her a book of potential suspects, then slammed his hand on the table again and pointed at Porter’s photo, saying, “That’s him right there, right?”

None of these events were disclosed either, the motion states.

“Don’t you think I think about that man (Porter) every day? … 30 years he did,” Aviles said in the 2021 interview, the motion states.

The motion also alleges Mark Rogers, Bland’s drug partner, identified two men he believed were the two shooters and later indicated Porter was not involved. But that also was not turned over to the defense.

The trove of records underlying the motion was obtained through the work of investigator Jabbar Collins, himself an exoneree, during a bruising nine year Freedom of Information battle with the Queens DA’s office.

Jabbar Collins

Jesse Ward/for New York Daily News Jabbar Collins leaves Brooklyn Federal Court on July 28, 2014. (Jesse Ward for New York Daily News)

In 2021, Porter formally asked the DA’s Conviction Integrity Unit to review the case. When nothing came of it after two years, he opted to withdraw the application and go to court.

“It was taking an extended period of time and they indicated they had other issues ahead of it so we made the decision to move forward with the litigation,” Barli said.