On Thursday morning, a divided New York State Court of Appeals overturned Harvey Weinstein’s 2020 conviction for sex crimes and ordered a new trial. The 4–3 ruling turned largely on the original judge’s decision to let into court evidence of alleged crimes other than the ones for which jurors had been asked to assess Weinstein’s guilt or innocence. The court had permitted women to testify about allegations of sexual assault that were separate from the three for which he was charged. It had also ruled that Weinstein, should he testify, could be questioned about his wider history of alleged misconduct.

Harvey Weinstein has been accused by more than a hundred women of various forms of sexual harassment and assault, with many of their stories reported in The New Yorker, and detailed in my subsequent book and podcast, “Catch and Kill.” Thursday’s news was greeted with anguish by activists and by Weinstein’s alleged victims. “This is an on-going failure of the justice system—and the courts—to take survivors seriously and to protect our interests,” Ambra Gutierrez, one of Weinstein’s early accusers, said, in a statement.

But Thursday’s ruling was, to many legal spectators, unsurprising. The idea that juries should consider only the crimes charged in a given case, and that evidence of other bad acts should be excluded, is a foundational principle of criminal law, designed to protect defendants from the unfair presumption of guilt. In New York, the precept is embodied in the Molineux rule, named for a 1901 case in which an appeals court overturned a verdict that found a chemist named Roland Molineux guilty of murder by cyanide poisoning. The appeals court held that the trial court’s admission of allegations related to an earlier, unrelated killing had invited jurors to consider the defendant’s general propensity for crime, rather than the facts at hand. This principle of fairness is simple. The intricacies of how it should be implemented are, as Thursday’s decision underscores, complicated. There are vast exceptions to the general prohibition of evidence of uncharged acts: the federal rules of evidence contain an exception for sex crimes, where, the logic goes, criminal conduct often hews to a pattern. In New York, which has not adopted that federal exception, case law has generally followed the Molineux holding, which allowed jurors to consider evidence of other, uncharged crimes if “it tends to establish (1) motive; (2) intent; (3) the absence of mistake or accident; (4) a common scheme or plan embracing the commission of two or more crimes so related to each other that proof of one tends to establish the others; (5) the identity of the person charged with the commission of the crime on trial.” But William Werner, the judge who wrote the Molineux decision, acknowledged with some prescience that “the exceptions to the rule cannot be stated with categorical precision.”

Thursday’s decision reveals a court struggling to parse those exceptions. Writing for the majority, Judge Jenny Rivera argued that testimony from women with allegations other than the ones Weinstein was charged with “served no material non-propensity purpose,” and that allowing prosecutors to cross-examine Weinstein about unrelated acts “undermined” his right to testify. In a potent dissent, Judge Madeline Singas wrote, “The majority appears oblivious to, or unconcerned with, the distressing implications of its holding. Men who serially sexually exploit their power over women—especially the most vulnerable groups in society—will reap the benefit of today’s decision. Under the majority’s logic, instances in which a trafficker repeatedly leverages workers’ undocumented status to coerce them into sex, or a restaurant manager withholds tips from his employees unless they perform sexual acts becomes a series of individual ‘credibility contests’ and unrelated ‘misunderstandings.’ After today’s holding, juries will remain in the dark about, and defendants will be insulated from, past criminal acts, even after putting intent at issue by claiming consent. Ultimately, the road to holding defendants accountable for sexual assault has become significantly more difficult.”

Harvey Weinstein is unlikely to be a free man anytime soon, regardless of the outcome of any potential new trial in New York. He must still serve a separate, sixteen-year sentence for a conviction in California, for raping an actress in a Beverly Hills hotel room. David Ring, a lawyer for Evgeniya Chernyshova, who was identified as Jane Doe 1 in the California case, said Thursday, “She and I are confident that Weinstein’s Los Angeles conviction for rape will be upheld.”

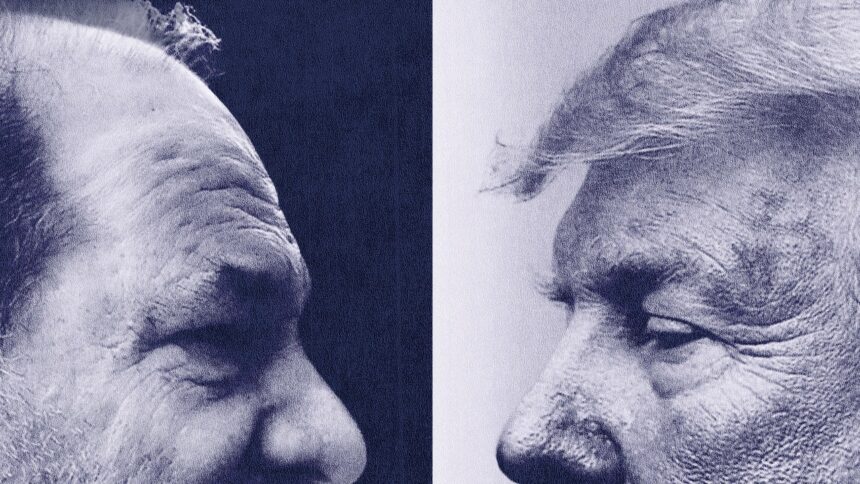

But the way that case law evolves on this question is important—and not just to the future of sex-crime cases. The ongoing hush-money case against Donald Trump, in New York, turns on evidence about acts for which he is not being charged.Trump faces thirty-four counts of business fraud related to a payment from his attorney Michael Cohen to the adult-film actress Stephanie Clifford, whose screen name is Stormy Daniels. But the judge in that case, Juan Merchan, has also admitted evidence of other payments, made by American Media Inc., as the parent company of the National Enquirer was known at the time (it has since merged with another firm, rebranded as A360 Media, and for years has tried to sell the Enquirer), that the prosecution says establish motive, intent, and what it describes as a broader conspiracy to sway the election. This week has been dominated by testimony from David Pecker, the former chief executive at A.M.I., on payments by the tabloid company to “catch and kill” a rumor that Trump fathered a child with an employee and the story of an affair he had with a Playboy model, Karen McDougal. Should Trump take the stand, Merchan has also allowed prosecutors to ask him about other cases against him: a fraud case in New York against his business and civil suits for sexual abuse and defamation brought by the writer E. Jean Carroll, all of which resulted in rulings against him. Elsewhere in the case, Merchan has denied requests from prosecutors to introduce evidence related to uncharged behavior, deeming broader information about Trump’s history of alleged sexual misconduct overly prejudicial and insufficiently relevant.

Merchan’s application of the Molineux rule in Trump’s case is, on its face, less controversial than the admission of uncharged assault allegations during Weinstein’s trial. Cohen’s payment to Clifford is deeply enmeshed in Trump’s broader alliance with the National Enquirer, which provides essential context for understanding that transaction’s intent. But the case’s reliance on evidence of uncharged activity will nevertheless afford Trump and his team ample opportunity to push back—arguing, as he has already begun to, in loud and repeated apparent violation of a gag order, that his prosecution has been unfairly skewed by political zeal, and potentially drawing the trial into the thicket of legal questions that brought down Weinstein’s New York verdict. ♦