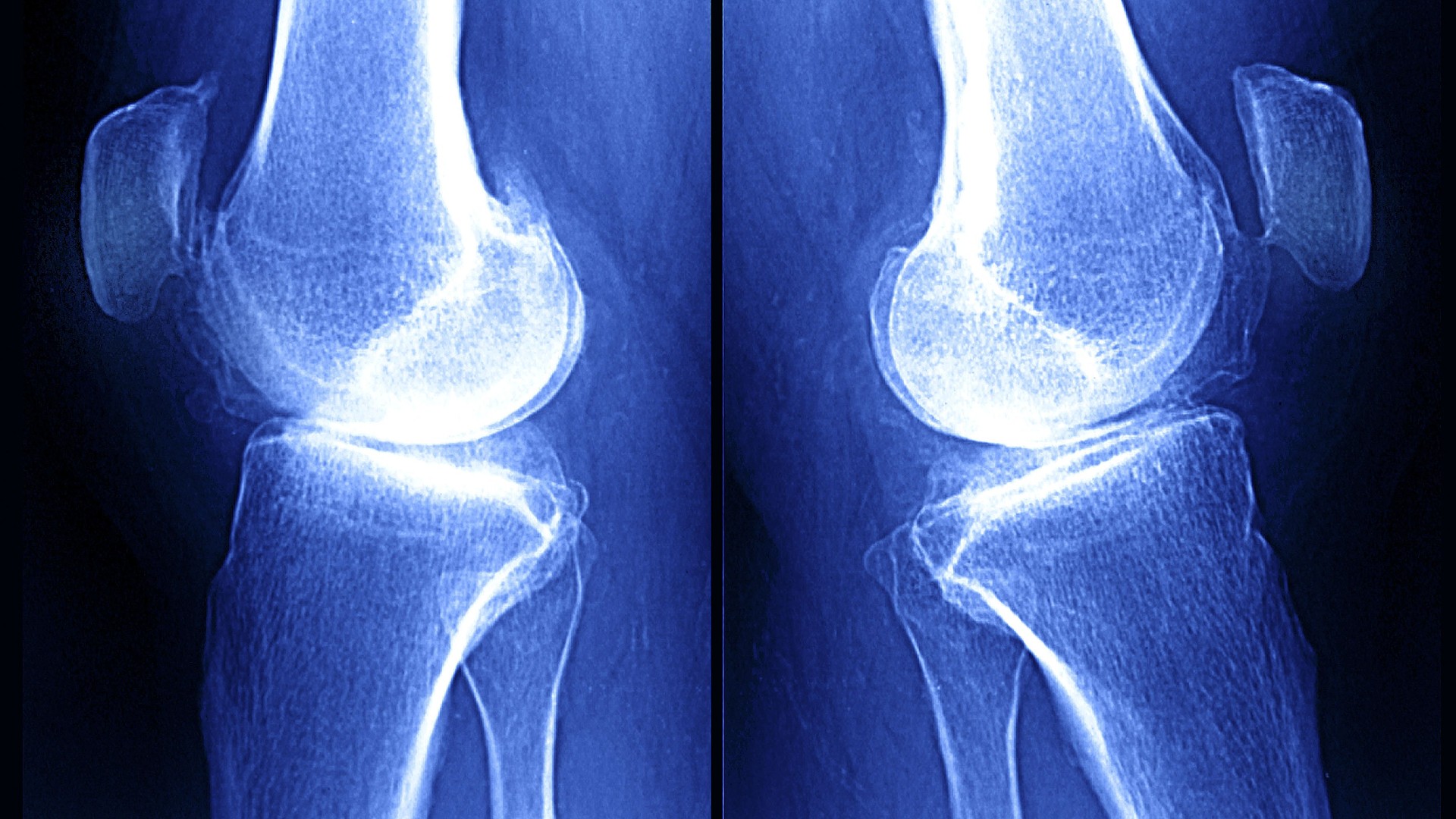

A simple blood test may be able to detect knee osteoarthritis in people who’ve yet to develop any symptoms — and up to eight years before an X-ray would be able to detect changes in their bones — scientists say.

In a new study, researchers analyzed the blood of 200 white women who had no symptoms of osteoarthritis when their blood was first sampled and were deemed “low-risk” of developing it. Their risk level was based on traditional risk factors, such as having a history of knee injury or a prior knee surgery.

They then analyzed the same people using the new test, which looked at proteins circulating in blood to predict people’s risk. As few as six bloodborne proteins could be used to accurately predict who would go on to develop knee osteoarthritis within 10 years, the researchers reported in a paper published Friday (April 26) in the journal Science Advances.

In some cases, the test could predict the disease up to eight years before an X-ray could detect signs of it. This is potentially a big improvement, as X-rays are currently the gold-standard diagnostic approach for osteoarthritis. The researchers say this early detection is important, because although there is no cure for the disease, there are preventative measures that can slow its progression. These include lifestyle factors such as engaging in low-impact exercise and maintaining a healthy weight, and taking medications that can relieve symptoms.

Related: Detecting cancer in minutes possible with just a drop of dried blood and new test, study hints

Spotting osteoarthritis earlier might therefore act as a “wake-up call” for people to engage in these preventive therapies, Dr. Virginia Byers Kraus, lead study author and a professor of medicine at Duke University in North Carolina, told Live Science. This could help avert the development of downstream complications, such as pain, disability and the need for joint replacement, she said.

Someday, the findings could also help scientists develop new, more-effective preventative treatments for the disease, Kraus added. Such treatments might target the proteins in the blood that are associated with the condition, for instance.

Osteoarthritis is the most common form of arthritis, and it affects more than 32.5 million adults in the U.S. It was originally known as a “wear and tear” disease because it occurs when cartilage within a joint — usually in the hands, hips and knees — breaks down. This causes the underlying bone to change over time, leading to pain, stiffness and swelling.

However, evidence now suggests that inflammation is an integral driver of the joint damage seen in osteoarthritis. This means that there could be “biomarkers,” or measurable signs in the body, that could signal that the disease is kicking off long before structural damage is picked up by an X-ray.

In the new study, Kraus and colleagues analyzed two sets of blood samples from an established cohort of white, middle-aged women in the U.K. who have been assessed annually for osteoarthritis since 1989. The team looked at 200 women from this cohort who were matched in terms of their age and body mass indices (BMI). After being monitored for 10 years, half of the women went on to be diagnosed with the disease and half did not.

Using artificial intelligence, the researchers identified six proteins in the blood samples that appeared to indicate whether a person would go on to get osteoarthritis. The blood samples in the analysis were taken either eight or four years prior to a person’s diagnosis. The flagged proteins are involved in promoting inflammation and in hemostasis, an early step in the body’s response to injury.

To determine whether the test was accurate, the team used a mathematical benchmark called area under the curve (AUC). An AUC below or equal to 50% means that a test cannot discriminate between people with or without the disease. Higher than 70% is considered “acceptable” performance and above 80% is “excellent.” The six proteins in the new study garnered an AUC of 77% — that’s compared to about 50% for predictions based on a person’s age and BMI and 57% for predictions based on knee pain.

These are promising early results, but the test won’t be rolled out in clinics any time soon, Kraus said. The team now needs to study whether this success can be replicated in men, as well as in people of other ethnicities. Women are more likely to develop osteoarthritis than men, especially after the age of 50.

After that, clinical trials for new treatments might be on the horizon, Kraus said. These biomarkers could theoretically be used to measure whether certain drugs halt the progression of osteoarthritis. If successful in animal models, such drugs could then be tested in people who may be at risk of developing the condition.

Ever wonder why some people build muscle more easily than others or why freckles come out in the sun? Send us your questions about how the human body works to community@livescience.com with the subject line “Health Desk Q,” and you may see your question answered on the website!