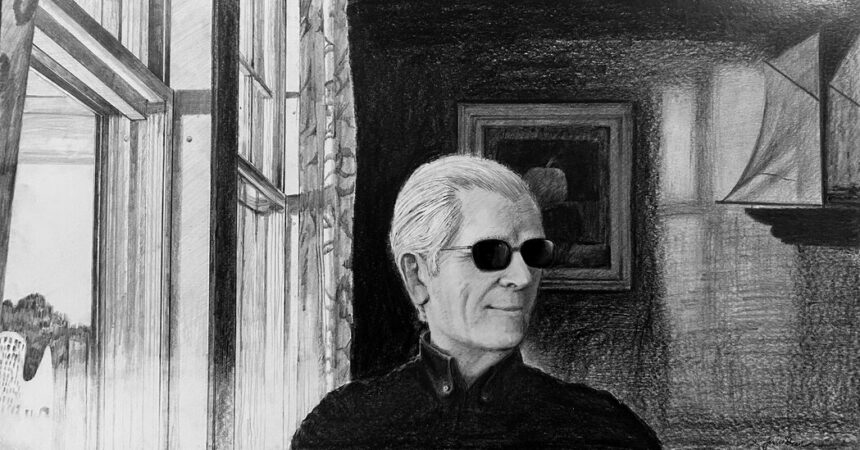

James Dean, a landscape painter who ran a NASA program that invited artists like Robert Rauschenberg, Norman Rockwell and Jamie Wyeth to document aspects of the Mercury, Gemini and Apollo projects, died on March 22 in Washington. He was 92.

His son Steven confirmed the death, at an assisted living facility.

From the final Mercury mission in 1963 until 1974, Mr. Dean gave dozens of artists access to astronauts, to areas near the launchpads at Cape Canaveral (and the Kennedy Space Center) and to ships that recovered astronauts after their ocean splashdowns.

Mr. Dean believed that artists offered a perspective that could not be found in photographs.

“Their imaginations enable them to venture beyond a scientific explanation of the stars, the moon and the outer planets,” Mr. Dean and Bert Ulrich wrote in their book, “NASA/ART: 50 Years of Exploration” (2008).

One night before L. Gordon Cooper blasted off on the last Mercury mission in May 1963, Mr. Dean allowed the painters Peter Hurd and Lamar Dodd to work from a field near the rocket’s launchpad, and provided them with huge lamps for illumination.

A security guard who saw the two artists amid the bushes with their paints and brushes quickly determined that they did not pose a threat — and escorted them to the top of the launchpad, where they looked inside the Mercury capsule, which gave Mr. Dodd the inspiration for his abstract gouache painting, “Max Q.”

In 1965 Jamie Wyeth, then 19, painted “Support,” a watercolor of the launch of Gemini 4 from a nearby gantry, the massive structure that encloses and services rockets before they lift off.

“Jamie went off to the edge and let his legs hang over, and he’s painting like he’s sitting on a dock up in Maine someplace,” Mr. Dean said in an interview in 2019 with Carolyn Russo, the art curator at the National Air and Space Museum.

Mr. Rauschenberg roamed the space center’s grounds in the weeks before the Apollo 11 mission that landed the first men on the moon.

“He didn’t bring a sketch pad or anything like that with him but what he wanted to do was look at our photo files to experience the action real-time,” Mr. Dean told Ms. Russo.

The experience led Mr. Rauschenberg to create “Stoned Moon,” a series of 34 lithographs, including “Sky Garden,” in which he superimposed a negative image of the Saturn 1-B rocket, with many of its parts labeled, over images of it blasting off.

In the hours before Apollo 11 launched on July 16, 1969, Mr. Dean got permission for the illustrator Paul Calle to sketch Neil Armstrong, Col. Buzz Aldrin and Lt. Col. Michael Collins having breakfast and then suiting up — the only artist allowed in those spaces.

James Daniel Dean was born on Oct. 14, 1931, in Fall River, Mass. His father, John, was a pastry chef. His mother, Sadie (Griffin) Dean, managed the home.

James recognized that he had artistic talent in high school when a history teacher told students to draw their homework, and he began sketching airplanes and ships. In 1950, he entered the Swain School of Design in New Bedford, Mass., and graduated in 1956, with time in between for his Army service in Panama.

He was hired as a graphic designer in the Secretary of Defense’s office; five years later, he joined NASA’s office of Educational Programs and Services. In 1963, a year after James Webb, the NASA administrator, created the fine art program, Mr. Dean was named its founding director, one of his many responsibilities in the office.

While Mr. Dean handled the art program’s logistics, Hereward Lester Cooke, a curator of painting at the National Gallery of Art, reached out to the artists, who were paid $800 each. They collaborated on the 1971 book, “Eyewitness to Space,” a collection of Apollo-related paintings and drawings.

“Jim had the foresight to know that artists would make an important contribution to the space age,” Mr. Ulrich said by phone. “The history of the agency unfolds through art and through the eyes of the artists.”

The concept of commissioning art at an agency devoted to science was not universally accepted early on, Mr. Dean recalled. He told The Orlando Sentinel in 1983 that some space technicians “regarded the artists with amused tolerance.”

He added, “Later as they saw their space hardware converted by the artists’ imagination and skill into images of fantasy and beauty, they increasingly became respectful.”

The artwork led to exhibitions in 1965 and 1969 and to several traveling tours.

Mr. Dean — who referred to himself as the “other” James Dean to differentiate himself from the actor — left NASA in 1974 to join the Air and Space Museum (which opened two years later), as the curator of art under Colonel Collins, the Apollo 11 astronaut who was its director.

Mr. Dean was in charge of transferring some 2,000 paintings and drawings from NASA to the museum as well as preparing exhibits and acquiring other artworks. He also contributed paintings of the space shuttle program to NASA.

He retired in 1980 to focus on his own painting from a studio in Alexandria, Va. He also designed stamps for the U.S. Postal Service, including one in 1985 that celebrated Frederic Bartholdi, who sculpted the Statue of Liberty.

His friendship with Colonel Collins resulted in Mr. Dean creating sketches that depict NASA’s history in “Liftoff: The Story of America’s Adventure in Space” (1988).

In addition to his son Steve, Mr. Dean is survived by another son, Richard; three grandchildren; and four great-grandchildren. His wife, Rita (Williams) Dean, whom he married in 1952, died in 2019. His son James died in 2018.

Mr. Dean arranged for Mr. Rockwell, whose paintings were renowned for their nostalgic evocations of small-town America, to meet the astronauts John Young and Virgil (Gus) Grissom during a countdown demonstration test before their Gemini 3 flight in 1965.

Mr. Rockwell, who was working for Look magazine at the time, left with photographs of the two astronauts. But after returning to his studio in Stockbridge, Mass., he realized that he needed more details about their spacesuits. He asked Mr. Dean for one.

Mr. Dean’s request was initially denied because material inside the suit was classified and could not be mailed. So he contacted Joseph W. Schmitt, a suit technician, who brought one to Stockbridge. Mr. Schmitt stayed for a week as Mr. Rockwell painted Mr. Young and Mr. Grissom suiting up.

When the painting was being hung at the National Gallery for an exhibition in 1965, Mr. Dean asked John Walker, the museum’s director, what he thought of it.

“And he looked at me seriously and he said, ‘I never knew Norman Rockwell had such quality,’” Mr. Dean told Ms. Russo. The next morning, Mr. Dean called Mr. Rockwell to tell him what Mr. Walker had said.

“He said, ‘Oh, now I can die happy.’”