“We’re seeing a bunch of EV manufacturers come here,” said Michael Adriaanse, “and they should be union.” Adriaanse organizes with the Blue Oval Good Neighbors Committee. In rural, working class Black communities in west Tennessee, this labor and community coalition is mobilizing to bargain with Blue Oval City, a Ford joint venture electric vehicle plant that’s the recipient of the largest public investment the state of Tennessee has ever made, with an added $9.2 billion in funding from the Department of Energy. The VW victory has given workers hope for their efforts to negotiate good jobs and community benefits with the EV industry, he added. But it’s going to be hard won.

“Anti-union sentiment across the country is virulent, and laws across the country don’t support unionization,” said Vonda McDaniel, who serves as a part of the Blue Oval coalition and is president of the Middle Tennessee Central Labor Council. Lawmakers in Tennessee, Georgia, and Alabama passed bills just this year and last year barring state incentives to companies that voluntarily recognize unions. In 2022, Tennessee enshrined right-to-work into its constitution. The prospect of this election had Southern governors running scared, so much so that the governors of Tennessee, Texas, South Carolina, Alabama, and Georgia wrote a joint public condemnation of the union drive. In Alabama, which boasts the seventh highest poverty rate in the country, Governor Kay Ivey lambasted UAW, saying that “the Alabama model for economic success is under attack.” Research has shown that any economic growth in right-to-work states tends to benefit the already wealthy.

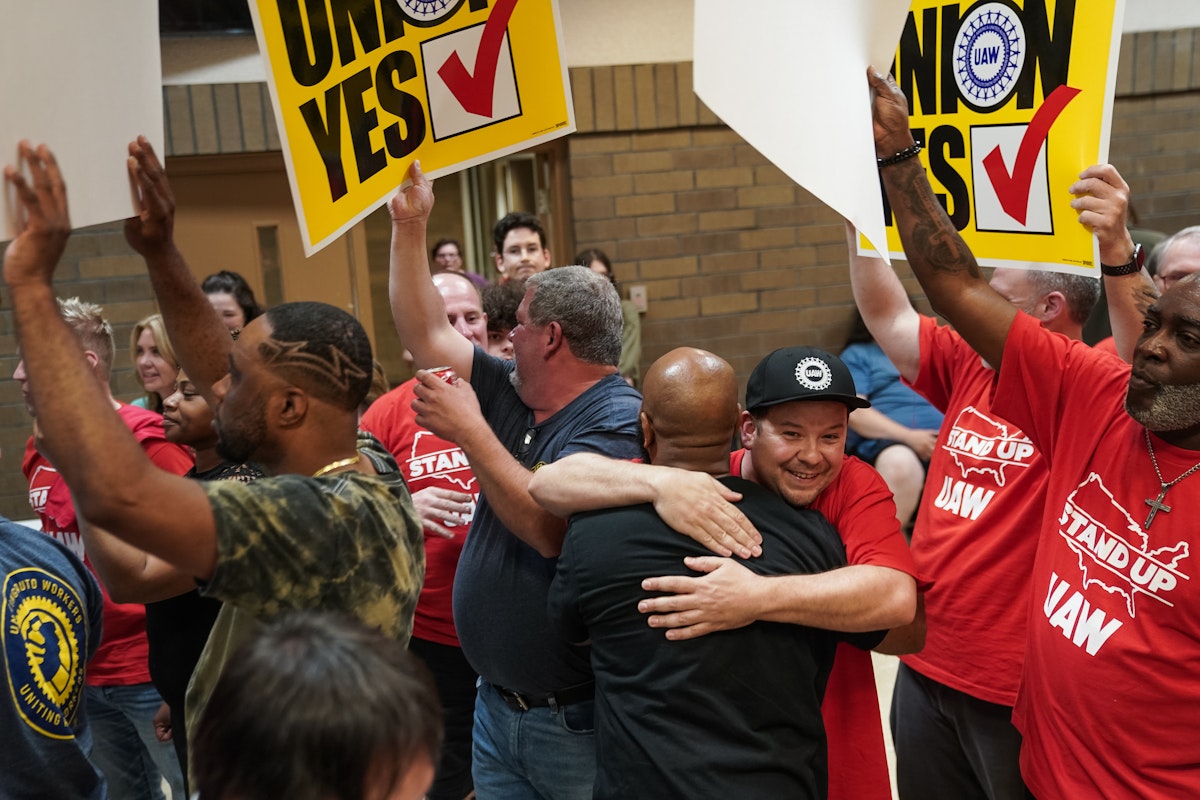

In its previous attempts to organize Volkswagen, the UAW attempted a top-down strategy, where they tried to simply persuade Volkswagen to recognize the union. The UAW employed a different strategy this time, a bottom-up strategy that truly involved deep organizing in the plant. “This has to be personal, person to person, door to door,” McDaniel said.