It’s the thing everyone always asks about. It used to weigh on Aidan Knipe. Some aspects of being a coach’s son are unavoidable.

But for the Long Beach State setter, it was never about the external pressure of playing for his father, head coach Alan Knipe. It was what he would do under that weight.

“I just had to play for who I was,” Aidan said, “and prove that I belonged here.”

Despite any outside scrutiny, the redshirt senior setter has cemented his place in the Long Beach State record books. Aidan, just the eighth player in Long Beach State history with 3,000 career assists, leads the second-seeded Beach into the NCAA tournament at 5 p.m. Tuesday against No. 7 seed Belmont Abbey (21-4) at Walter Pyramid. Long Beach State (29-2) is hosting the tournament for the first time since 2019, when it used the home court advantage to help win its latest NCAA title.

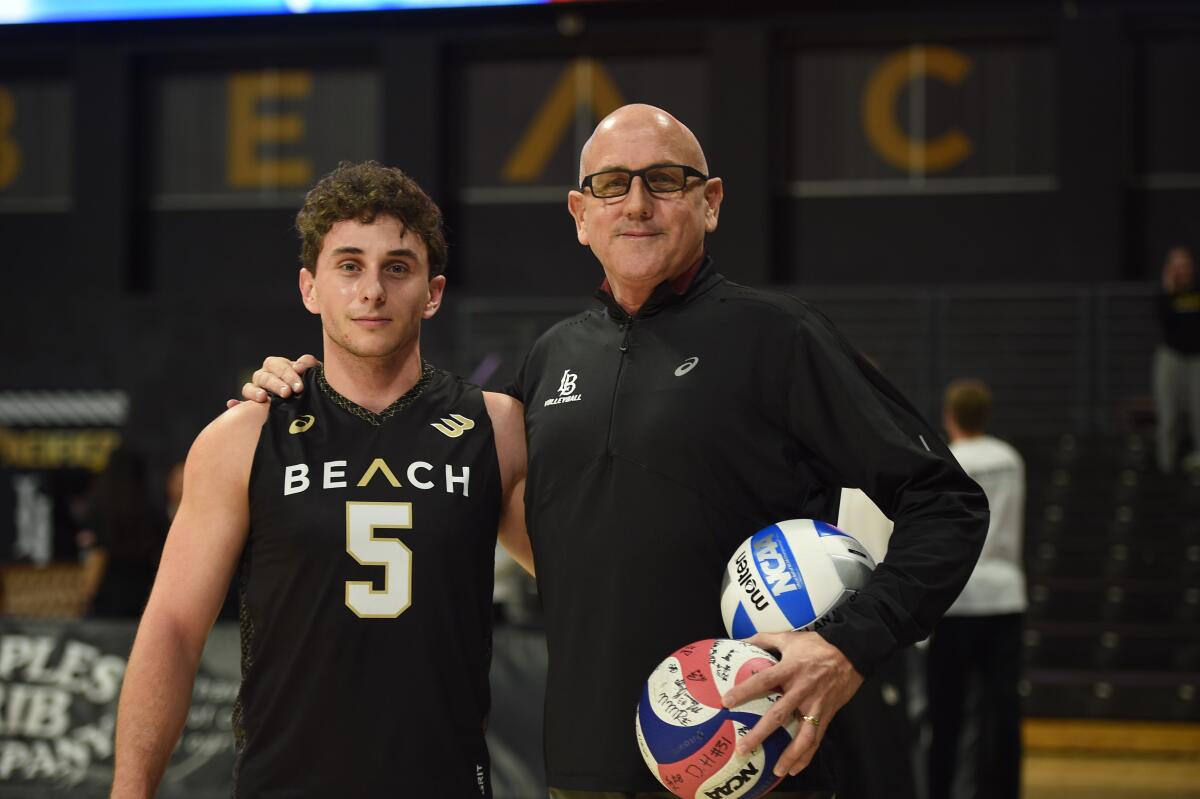

Aidan Knipe, left, stands next his father, Long Beach State coach Alan Knipe, after the coach earned his 400th career win.

(Courtesy of John Fajardo / Long Beach State Athletics)

Aidan couldn’t be at the Pyramid for the championship match that year. It is seemingly one of the few major events in program history he’s missed.

The Huntington Beach High alumnus, who was playing in the CIF-Southern Section playoffs when Long Beach defeated Hawaii in four sets to win its second consecutive NCAA title, has been attending men’s volleyball matches almost since birth. His first trip out of the home as a newborn was to the Pyramid, he proudly points out . It was the same year his father took over as the head coach.

In two decades at his alma mater, Alan has built Long Beach State into a volleyball powerhouse. He is the only person to be involved in all three of Long Beach State’s national titles, from being the star outside hitter in 1991 to coaching in 2018 and 2019.

But this experience with Aidan, Alan said, “has been the most meaningful in my entire coaching and playing career.”

Alan relished coaching his sons — Aidan and younger brother Evan, who is also a student at Long Beach State — in youth sports from soccer to baseball to football. But when Aidan started showing increased interest and aptitude in volleyball, Alan stepped back from the sidelines of his son’s games. As Aidan grew into a college prospect and played with USA Volleyball for five years, Alan knew it was the right choice to not coach his son during his juniors career.

He wanted to save their time for college.

Aidan always knew it would be Long Beach. But, with his father encouraging him to explore other schools, there was still a recruiting pitch from the Long Beach staff. Aidan even took an official visit. Alan, who grew up playing soccer and was coached by his father, knew he needed to delicately balance father and son vs. coach and player.

“When Aidan got here, I always tried to say I don’t want it to be harder on him than anybody else,” Alan said. “I just don’t want it to be easier than anybody else.”

The key to their dynamic may be separation, even during the season when they spend nearly every day in the gym together. Aidan lives with teammates in Long Beach. Associate head coach Nick MacRae, the team’s offensive coordinator, works directly with Aidan on the technical points of setting, as was the case for previous setters in the program. Alan is left to coach the team from a wide lens. He doesn’t see his son any more than any other player on the team.

Despite the separation behind the scenes, outside assumptions of favoritism are unavoidable in many father-son dynamics. If Simon Torwie saw a son playing for his father on any other team, the Long Beach State senior middle blocker said he might have the same ideas many internet critics have of Aidan’s position on the court. But Torwie, who counts Aidan as one of his closest friends on the team, said the notion that the setter is successful or gets to play only because he shares a last name with his head coach is “completely wrong.”

“I’ve seen it every single day, I’ve seen it on off days, I’ve seen their relationship outside the court, it’s not fair to just reduce it all to that,” said Torwie, the nation’s leading blocker at 1.366 per set. “Both of them are basically the hardest workers you could ever see.”

Long Beach State coach Alan Knipe talks to the team during an NCAA men’s volleyball tournament against UCLA in 2022.

(Marcio Jose Sanchez / Associated Press)

Aidan orchestrates the fifth-best offense in the country as the Beach, hitting 0.346%, won its third consecutive Big West regular season title, claimed its first conference tournament title since 2018 and enters the NCAA tournament as the only team with fewer than four losses this season.

After two seasons earning all-conference honorable mentions, Aidan picked up his first Big West first-team honor this season after averaging 10.23 assists per set with career bests in blocks (0.69) and digs (1.52) per set. A chronic injury that resulted in ankle reconstruction surgery after the 2021 season hampered much of Aidan’s first two seasons. While undersized at a wiry 6 feet 3 Aidan is one of the team’s best jumpers, Alan attests. Because of the surgery, Aidan was ground-bound for five months leading into his redshirt sophomore season. He still piloted the team to the national championship game in 2022.

“I want to be able to show that I can jump high and do all the things that the big guys can do,” Aidan said. “But at certain points I wasn’t able to do that. … I just kind of have to give up on being selfish in that sense and just provide whatever I can to the team.”

It’s no coincidence that Aidan’s career has taken off with his improved health. To set himself up for his best season, the 23-year-old dedicated himself to the weight room and lifted five times a week during the offseason. He refined his diet and is 20 pounds heavier than when Long Beach played in the NCAA semifinals last year.

Back in the NCAA tournament for the third consecutive year, Long Beach is trying to win its fourth national championship. Aidan has had this opportunity on his mind for years. When he took his official recruiting visit, the staff told him the Pyramid would host the NCAA tournament during his would-be fifth season.

Getting here required more detours than expected with the COVID-19 pandemic decimating the roster and almost instantly ending the program’s previous golden era that featured back-to-back titles in 2018 and 2019. The current senior class has carried the weight of the program without much veteran leadership, Alan said. They left it better than they found it, the coach added.

That, after a career of trying to carve out his own legacy, is why Aidan belongs at Long Beach State.

“He is the one that we need on court,” Torwie said. “He deserves it and he has worked his ass off to be that guy. …. I would not want anyone else to set for me.”