The year 2024 is one of the biggest election years in history, with billions of people going to the polls around the globe. Although elections are considered protected, internal state affairs under international law, election interference between nations has nonetheless risen. In particular, cyber-enabled influence operations (CEIO) via social media—including disinformation, misinformation or “fake news”—have emerged as a singular threat that states need to counter.

Influence ops initially skyrocketed into public awareness in the aftermath of Russian election interference in the 2016 U.S. presidential election. They have not since waned. Researchers, policy makers and social media companies have designed varied approaches to counter these CEIOs. However, that requires an understanding, often missing, of how these operations work in the first place.

Information, of course, has been used as a tool of statecraft throughout history. Sun Tzu proposed more than 2,000 years ago that the “supreme art of war” is to “subdue the enemy without fighting.” To that end, information can influence, distract or convince an adversary that it is not in their best interest to fight. In the 1980s, for example, the Soviet Union initiated Operation Infektion/Operation Denver aimed at spreading the lie that AIDS was manufactured in the U.S. With the emergence of cyberspace, such influence operations have expanded in scope, scale and speed.

On supporting science journalism

If you’re enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

Visions of cybergeddon—including catastrophic cyber incidents wreaking havoc on communications, the power grid, waters supplies and other vital infrastructure, resulting in social collapse—have captured public imagination and fueled much of the policy discourse (including references to a “cyber Pearl Harbor”).

Yet, cyber operations can take another form, targeting the humans behind the keyboards, rather than machines through code manipulation. Such activities conducted through cyberspace can be aimed at altering an audiences’ thinking and perceptions, with the goal to ultimately change their behavior. Organizing political rallies in an adversary state would be an example of mobilization (behavioral change). As such, modern cyber-enabled influence operations represent a continuation of international competition short of armed conflict. As opposed to offensive cyber operations that might hack networked systems, shut down a pipeline or interrupt communications, they focus on “hacking” human minds. That comes in particularly handy when a foreign power wants to meddle in someone else’s domestic politics.

CEIOs operate by establishing self-sustaining loops of information that can manipulate public opinion and fuel polarization. They are “a new form of “divide and conquer” applied to geopolitical condition of competition rather than in war,” I recently argued with a co-author in the Intelligence and National Security journal.

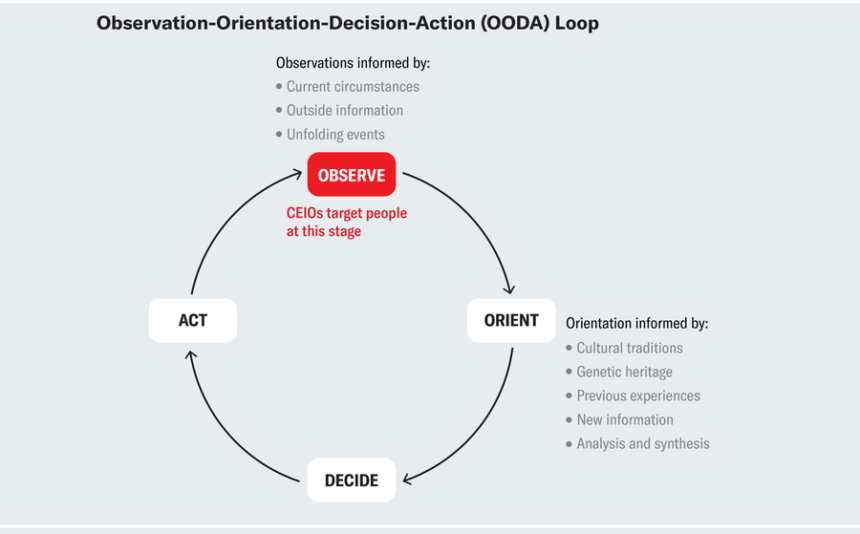

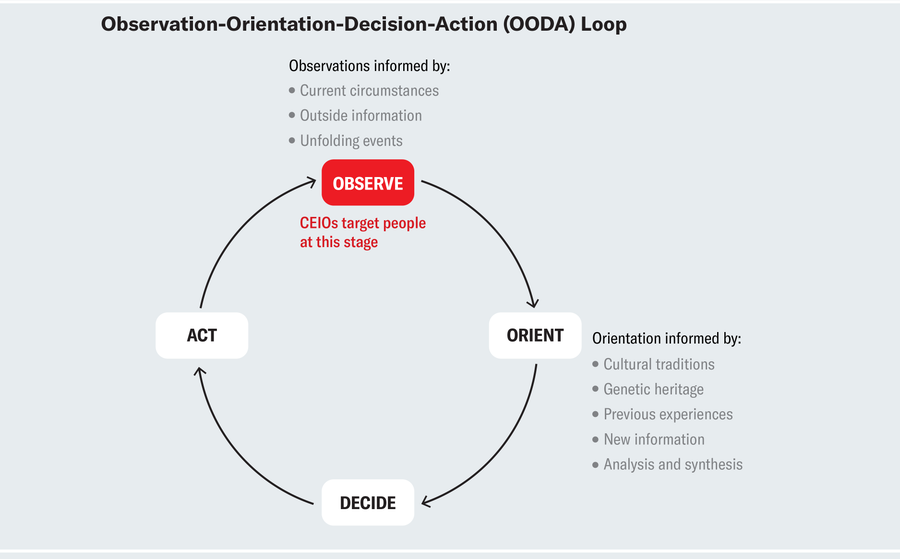

But how do these operations work? In order to understand that, we can use the military concept of the observation-orientation-decision-action (OODA) loop, which is widely used in planning strategy and tactics. The model helps explain how individuals arrive at decisions relevant to daily life: individuals in a society (us) take information from our environment (observation) and make strategic choices as a result. In the case of a dogfight (close-range aerial battle), the strategic choice would lead to pilot’s survival (and military victory). In day-to-day life, a strategic choice might be selecting the political leader that would best represent our own interests. Here, changing what is being observed by injecting additional information into the observation part of the OODA loop can have significant repercussions. CEIOs aim to do precisely that, by feeding different parts of the public with targeted messages at the observation stage aimed to ultimately change their actions.

Amanda Montañez; Source: A Discourse on Winning and Losing, by John R. Boyd; Air University Press, 2018

So how do CEIOs interrupt the OODA loop using social media? Cyber-enabled influence operations function on common principles that can be understood through an identification-imitation-amplification framework. First, “outsiders” (malicious actors) identify target audiences and divisive issues through social media microtargeting.

Following this, the “outsiders” may pose as members of the target audience by assuming false identities, through imitation which increases their credibility. An example is the 2016 Russian CEIO on Facebook, which bought ads to target U.S. audiences, manned by the infamous “troll factories” in St. Petersburg. In these ads, trolls assumed false identities and used the language that suggested that they belonged to the targeted society. Then they try to achieve influence through messages designed to resonate with target audiences, promoting a sense of in-group belonging (at the expense of any larger assumed community, such as the nation). Such messages may take the form of traditional disinformation, but may also employ factually correct information. For this reason, using the term CEIO, instead of “disinformation,” “misinformation” or “fake news,” might provide more analytical precision.

Finally, tailored messages are amplified, both in content (increasing and diversifying the number of messages) and by increasing the number of target groups. Amplification can also occur via cross-platform posting.

Consider an example: a post by a recently enlisted soldier who recounts their lived experience of seeing September 11th on TV and says that it was this event that motivated them to join the military. This is a post that was shared by the Veterans Across the Nation Facebook page. The content of this post may be entirely fabricated, and VAN may not exist “in real life.” However, such a post, while fictional, can have the emotive impact of authenticity, particularly in how it is visually presented on a digital media platform. And it can be leveraged for purposes other than promoting a shared sense of patriotism, depending on to what content it becomes linked and amplified through.

In its CEIO using Facebook, the Russian Internet Research Agency targeted diverse domestic audiences in the U.S. through specifically crafted messaging aimed at interfering in the 2016 election, as recounted in the Mueller Report.Reportedly, 126 million Americans were exposed to Russian efforts to influence their views, and their votes, on Facebook. Different audiences heard different messages, with groups identified using Facebook’s menu-style microtargeting features. Evidence shows that the majority of Russian-bought ads on Facebook targeted African Americans with messages that did not necessarily contain false information, but rather focused on topics including race, justice and police. Beyond the U.S., Russia reportedly targeted Germany, as well as the U.K.

To effectively make strategic decisions, individuals must correctly observe their environments. If the observed reality is filtered through a manipulated lens of divisiveness, manageable points of social disagreement (expected in healthy democracies) can be turned into potentially unmanageable divisions. For example, the popular emphasis on polarization in the U.S. ignores the reality that most people are not as politically polarized as they think. Trust in institutions can be undermined, even without the help of “fake news.”

As the identification-imitation-amplification framework highlights, the question of who can legitimately participate in debates and seek to influence public opinion is of crucial importance and has a bearing on what is the “reality” that is being observed. When technology allows outsiders (foreign malicious actors) to credibly pose as legitimate members of a certain society, the potential risks of manipulation increase.

With about 49 percent of the global population participating in elections in 2024, we must counter CEIOs and election interference. Understanding imitation, identification and amplification is just the starting point. Foreign influence operations will utilize truthful information to sway public opinion. We must think deeply about what that means for domestic political affairs. Furthermore, if cyberspace provides access and anonymity facilitating influence operations aimed at swaying audiences and affecting elections, democracies must effectively limit that access to authentic, legitimate users while staying true to principles of free speech. This a hard task, one we urgently need to undertake.

This is an opinion and analysis article, and the views expressed by the author or authors are not necessarily those of Scientific American.