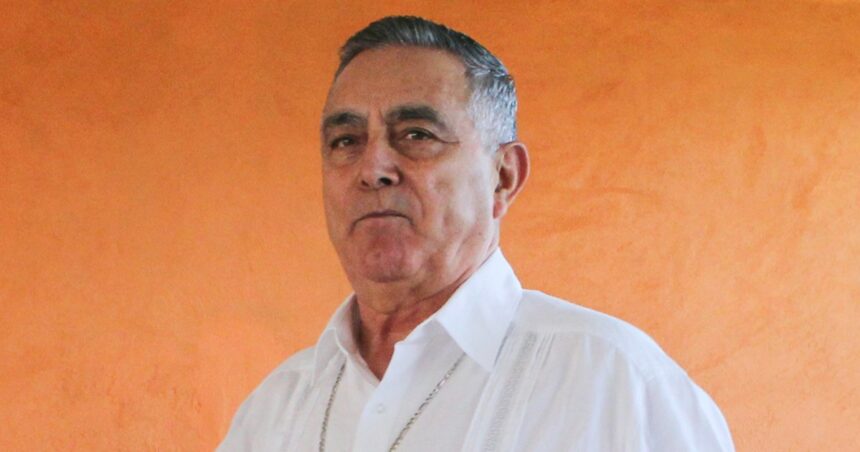

MEXICO CITY — A retired Roman Catholic bishop who was known for trying to mediate between drug cartels in Mexico was found and taken to a hospital after apparently being briefly kidnapped, the Mexican Council of Bishops said Monday.

The church leadership in Mexico said in a statement earlier that Monsignor Salvador Rangel, a bishop emeritus, disappeared on Saturday and called on his captors to release him.

But the council later said he “has been located and is in the hospital,” without specifying how he had been found or released, or providing the extent of his injuries.

Uriel Carmona, the chief prosecutor of Morelos state, where the bishop disappeared, said “preliminary indications are that it may have been an ‘express’ kidnapping.”

In Mexico, regular kidnappings are often lengthy affairs involving long negotiations over ransom demands. “Express” kidnappings, on the other hand, are quick abductions usually carried out by low-level criminals were ransom demands are lower, precisely so the money can be handed over more quickly.

Earlier, the council said Rangel was in ill health, and begged the captors to allow him to take his medications as “an act of humanity.”

Rangel was bishop of the notoriously violent diocese of Chilpancingo-Chilapa, in the southern state of Guerrero, where drug cartels have been fighting turf battles for years. In an effort later endorsed by the government, Rangel sought to convince gang leaders to stop the bloodshed and reach agreements.

Rangel was apparently abducted in Morelos state, just north of Guerrero. The bishops’ statement reflected the very fine and dangerous line that prelates have to walk in cartel-dominated areas of Mexico, to avoid antagonizing drug capos who could end their lives in an instant, on a whim.

“Considering his poor health, we call firmly but respectfully to those who are holding Msgr. Rangel captive to allow him to take the medications he needs in a proper and timely fashion, as an act of humanity,” the bishops’ council wrote before he was found.

It was unclear who may have abducted Rangel. The hyper violent drug gangs known as the Tlacos, the Ardillos and the Familia Michoacana operate in the area. Nobody immediately claimed responsibility for the crime.

If any harm were to have come to Rangel, it would have been the most sensational crime against a senior church official since 1993, when drug cartel gunmen killed Bishop Juan Posadas Ocampo in what was apparently a case of mistaken identity during a shootout at the Guadalajara airport.

Prosecutors in Guerrero state confirmed the abduction but offered no further details, saying only they were ready to cooperate with their counterparts in Morelos. Morelos, like Guerrero, has been hit by violence, homicides and kidnappings for years.

In a statement, Rangel’s old diocese wrote that he “is very loved and respected in our diocese.”

In February, other bishops announced that they had helped arrange a truce between two warring drug cartels in Guerrero.

Rev. José Filiberto Velázquez, who had knowledge of the February negotiations but did not participate in them, said the talks involved leaders of the Familia Michoacana cartel and the Tlacos gang, which is also known as the Cartel of the Mountain.

Bishops and priests try to get cartels to talk to each other in hopes of reducing bloody turf battles. The implicit assumption is that the cartels will divide up the territories where they charge extortion fees and traffic drugs, without so much killing..

Earlier, the current bishop of Chilpancingo-Chilapa, José de Jesús González Hernández, said he and three other bishops in the state had talked with cartel bosses in a bid to negotiate a peace accord in a different area.

Hernández said at the time that those talks failed because the drug gangs didn’t want to stop fighting over territory in the Pacific coast state. Those turf battles have shut down transportation in at least two cities and led to dozens of killings in recent months.

“They asked for a truce, but with conditions” about dividing up territories, González Hernández said of the talks, held a few weeks earlier. “But these conditions were not agreeable to one of the participants.”

In February, President Andrés Manuel López Obrador said he approves of such talks.

“Priests and pastors and members of all the churches have participated, helped in pacifying the country. I think it is very good,” López Obrador said.

Critics say the talks illustrate the extent to which the government’s policy of not confronting cartels has left average citizens to work out their own separate peace deals with the gangs.

One parish priest whose town in Michoacan state has been dominated by one cartel or another for years said in February that the talks are “an implicit recognition that they (the government) can’t provide safe conditions.”

The priest, who spoke on condition of anonymity for security reasons, said “undoubtedly, we have to talk to certain people, above all when it comes to people’s safety, but that doesn’t mean we agree with it.”

For example, he said, local residents have asked him to ask cartel bosses about the fate of missing relatives. It is a role the church does not relish.

“We wouldn’t have to do this if the government did its job right,” the priest said.

In February, Rangel told The Associated Press that truces between gangs often don’t last long.

They are “somewhat fragile, because in the world of the drug traffickers, broken agreements and betrayal occur very easily,” Rangel said at the time.