Luck and art are clearest in retrospect. I arrived at Harvard as most eighteen-year-olds arrive at Harvard: with a grandiose sense of endeavor and a below-average understanding of the way that most things worked. Helen Vendler was one of a very few people on the English faculty whose name I recognized. I applied to take her freshman seminar on Walt Whitman, and got in—the first real coup (I thought) of my adulthood. The course met weekly for two hours, at a long oval table, with a water-fountain break halfway through, and, as the group resettled from this pause one day, I returned to my seat to find a student’s legs sticking out across the floor under the table. I leaned down and heard a gentle snoring. “Uhhh, Professor Vendler . . . ” another student exclaimed. Vendler looked down. “Oh—let him sleep,” she said, then added, “Students never get enough sleep.” In time, our classmate made a bashful reappearance, but by then Vendler had begun her lesson on “Crossing Brooklyn Ferry” and delivered a crucial message: the study of poetry and the living of life weren’t separate but a single way of being.

Vendler, who died last week, at ninety, served as The New Yorker’s poetry critic from 1978 to 1996, and the temptation, as always in the wake of extraordinary lives, is to install her promptly on the pantheon, with a likeness made in chilly stone. There is no exaggeration in calling her the most influential American poetry scholar of the past fifty years. She was as brilliant at illuminating the old as at championing the new; it is unusual for an academic who produces the definitive contemporary account of Shakespeare’s verse (as in “The Art of Shakespeare’s Sonnets”) or of Wallace Stevens’s weird, uninviting long poems (in “On Extended Wings”) to be the same writer who notices poets as distinct as Seamus Heaney, Jorie Graham, Rita Dove, and Ocean Vuong. Vendler didn’t follow literary or academic fashions. Nor did she operate, as some critics claim to, by intuition or “taste.” What she had was an almost tactile understanding of the ancient practice of creating poems as art, and—running her hands like a dressmaker along the back of their stitching, watching the way they draped and moved and caught the light—she could see not only what poets did but how they did it. When, in 2009, major poets (including Dove, who, in a notorious letters-column exchange, later took issue with Vendler’s negative review of an anthology she edited) contributed to a collection celebrating Vendler’s criticism, the volume was called “Something Understood.”

Vendler was said to work in the mold of I. A. Richards, the British critic associated with the founding of the so-called New Criticism and one of her most prized teachers in graduate school, at Harvard. She actively resisted the tendency to psychologize, politicize, or historicize textual interpretation. A poem was an art work standing on its own, and, as in a marvellous early piece in the magazine on Marianne Moore or her authoritative book-length study of Heaney, she traced a sensitive path between a poet’s biography and corpus, keeping her focus on the page, the line, the word. Reading Vendler often carried the thrill of watching someone solve a puzzle. She ended her exposition of Shakespeare’s “summer’s day” sonnet, one of the most overquoted in all of English literature, by pointing out an ingenious hidden pun, created by turning one letter upside down.

It was perhaps ironic, then, that Vendler’s presence on the page seemed incomplete; I always felt that her distinguishing qualities came through most strongly in the human bonds she made. (“It’s a very hard thing to be an exhibit when you’re a person,” she observed of Yeats while teaching “Among School Children,” an observation that might have reflected back on her.) She spoke in what used to be called the Harvard accent—the voice of Leonard Bernstein and George Plimpton, with “can’t” pronounced like the philosopher and “R”s melting away—and dressed like a New Englander (or my Californian’s idea of a New Englander), all floppy blazers and sensible slacks. She was an entrancing lecturer, precise, funny, in love with the work, and her longtime introductory poetry survey at Harvard, Poets, Poems, Poetry, had famously huge enrollment. (Happily, at least a few of her lectures can still be seen online.)

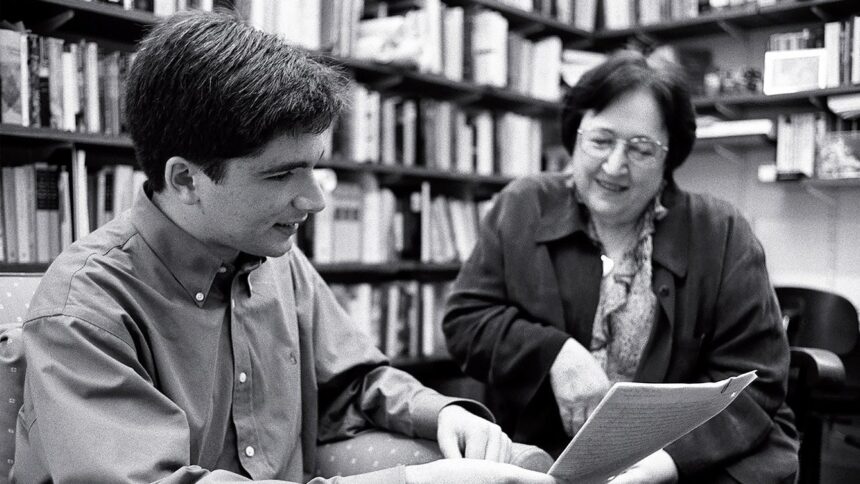

At close range, though, Vendler appeared—as with the floor sleeper—to relish taking people as they came. In the seminar, she bore down on every ghastly piece of writing we submitted, her tiny, spidery ballpoint cursive crawling down the margins of our papers and continuing onto the back of the last page. She implored us to come visit her during office hours. The first time I showed up, she opened a can of Diet Coke from a little refrigerator she kept, offered me the same, and began chatting about the “Parade’s End” tetralogy and other novels, on the premise that fiction was a subject about which she knew no more than we did. (This was, of course, untrue, though she once told our class that, when she was a young English professor parenting a child alone after the end of her marriage, she had reviewed some novels “for money,” and she still felt guilty about what she considered to be this imposture.) It was good to be an expert, but being a complete person, a full mind, meant passionate inexpertise, too. She seemed to see the writers and thinkers whom we could one day become.

The most sharply I can recall Vendler ever speaking was when one of us pointed out that some poets had troubled and unhappy lives. “Yes, but they are not to be pitied,” she nearly snapped back. “Because they have the much deeper fulfillment of creating lasting works of art.” In a milieu that seemed increasingly to measure success in terms of résumé, life style, and market share—we were the class that produced Facebook—the statement was a check. Vendler took seriously those who are often patronized, like students and artists, and, if she was ever patronizing, it was toward those usually heeded. (“You should never let editors rush you, Nathan,” she told me years later, after I’d begun to publish. “They always try, but it’s simply because they don’t know any better.”)

She had spent the first third of her own career brushed off by those who presumed to know better. After growing up with a love of poetry in a devout Catholic household in middle-class Boston, she had majored in chemistry at Emmanuel College, because books there seemed to be taught as moral statements on Christian ideals. When she was a graduate student in English, at Harvard, the chair of the department refused to let her enroll in Richards’s course. “You know we don’t want you,” he told her. “We don’t want any women here.” By the time Boston University granted her tenure, in 1969, she had taught at half a dozen places; she was in her fifties, and ensconced at this magazine, when Harvard hired her—after a tryout. She knew what it was to be underestimated and overburdened. She was one of the world’s great grousers about overwork. When our class returned from Thanksgiving break, we inquired after hers. “Well, it wasn’t much of a break,” she grumbled. “I baked a casserole, cleaned my house, and wrote forty-five thousand words of reviews.” Or that’s what I thought she said. Eventually, one of my roommates persuaded me that Vendler had probably said “four to five thousand words of reviews,” but it speaks to my faith in her capacities then that it seemed entirely plausible she’d produced half a critical collection between vacuumings.

Vendler, she made it clear, was with each of us not only in our seminar but for the future. When I began to publish more regularly, she was filled with suggestions and delight. She seemed to want to show us that it was possible to be a brilliant mind—an “exhibit”—and a human being not just concurrently but together. That was, if anything, what poetry was about.

I last saw Vendler a few years ago, before the pandemic, during a visit she made to New York to read at the Tibor de Nagy Gallery for an event organized in part by the Arion Press. A time before then, I had published an essay about Vendler and her decades of work with the Press’ founder, the master printer Andrew Hoyem. Vendler read that evening with Frank Bidart and Jonathan Galassi. At dinner, afterward, I sat next to Vendler, who, with an eightysomething’s sense of liberty, ordered an enormous pot of cheese fondue as her dinner. She was herself: avid, engaged, eager to talk about my writing and her reading outside poetry. She was being chased into old age by work, she lamented. Her beloved son was beginning to retire. “A son retiring before his mother—have you ever heard of such a thing?” she asked with barely concealed delight.

What I remember most vividly, though, is the walk from the gallery to the restaurant. It was a cool May evening. Vendler had been suffering a flare-up of bronchitis, and Bidart was having problems with his back, and the two of them fell a block behind the group, with me bringing up the rear. “People always say something is ‘a couple of minutes away’—they forget that exact distance matters to the old,” Vendler said. She would pause for a few moments to catch her breath; Bidart would wait. Then he’d rest, and she would do the same for him. The view I had treading behind them is one that I will always carry: the poet and the critic, slowly moving forward together, each pausing to wait for the other to catch up. ♦