In the 1930s, the United States produced a too-brief proletarian literary movement and at the center of it was Jack Conroy.

In the midst of the Depression, Conroy helped encourage a new generation of working-class writers.

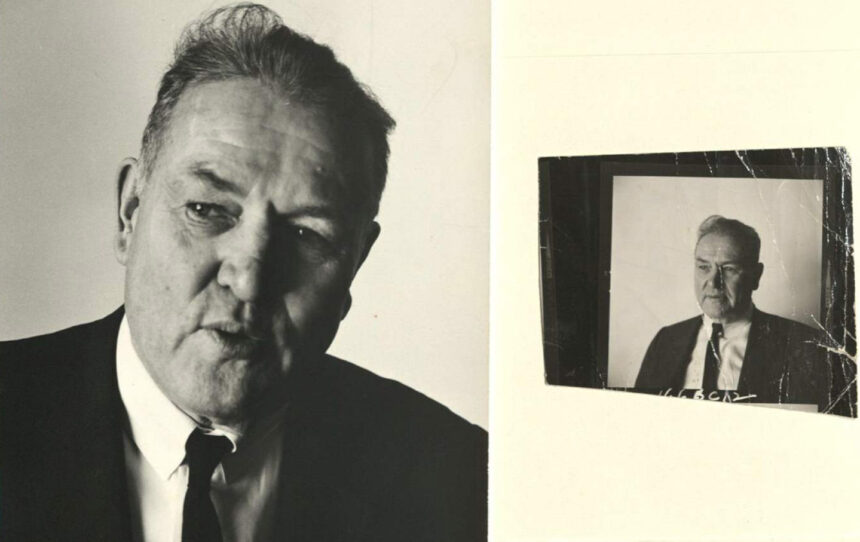

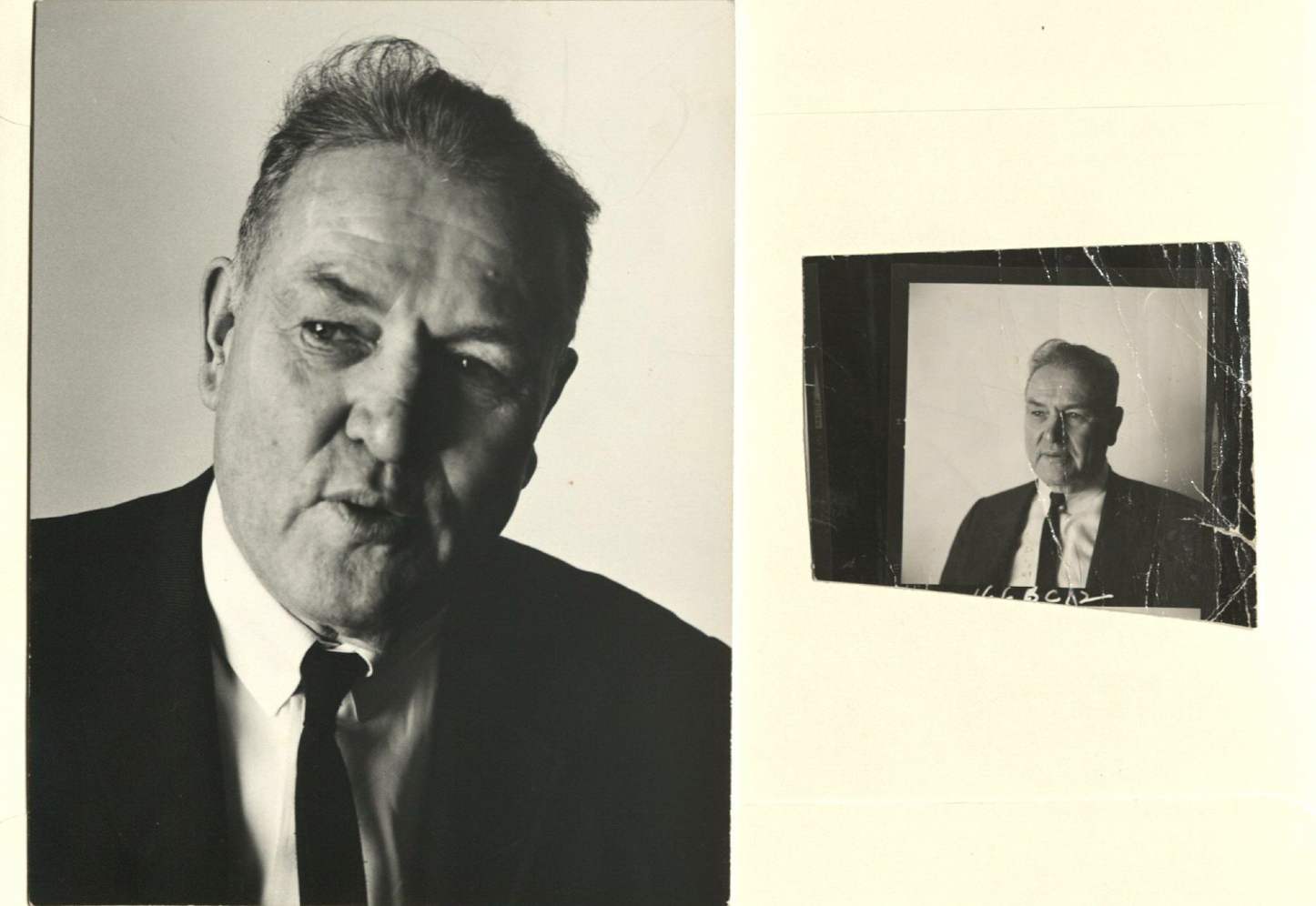

Jack Conroy

(Courtesy of Newberry Library)

Richard Wright called him the “old daddy of rebel writing,” but Jack Conroy was most often known by the nickname “the Sage of Moberly.” A wise man out in the Missouri hinterland, Conroy was the forgotten godfather of a revolutionary American literary movement that flourished briefly in the 1930s.

Six feet tall, barrel-chested, and with the booming voice of a longshoreman, Conroy was the editor of Rebel Poet magazine and eventually The Anvil, a leading left-wing literary publication of the decade. He was a writer, too, and penned dozens of short stories and workers’ sketches as well as two novels: The Disinherited and A World to Win. A collaborator with Harlem Renaissance poet Arna Botemps, Conroy was also an amalgamator of young literary ambition, from Joe Kalar to Richard Wright. He wanted to prove that the working class in America was an untapped source of liberatory poetics.

Most of Conroy’s literary production was accomplished in Moberly, Mo., usually after he’d spent hours in the sun digging ditches on a road crew or scrapping sheet metal in a factory. Conroy was a worker-writer, a hybrid literary entity who hammered out revolutionary prose, giving testimony to the disinherited and downtrodden of the Great Depression. He wanted to tell working people’s stories because he was one of them. “The American worker is not the clod he seems to be,” Conroy wrote in an editorial for Rebel Poet. “He has begun to think; when he gets into his full stride his footsteps will shake the earth and tumble down many a gaudy and gilded temple.”

Born in a coal-mining camp, Conroy had a brief childhood before entering the workforce at age 13, when he began an apprenticeship in the Wabash Railroad shops. While carrying the toolbox of the “car toad” mechanic and hauling away loose scrap, he sharpened his literary sensibilities through shop-side storytelling and his mother’s popular novels. Thanks to Moberly’s Carnegie Library, he read Edward Bellamy’s Looking Backward and Jack London’s People of the Abyss, but some of his earliest inspirations came from the humorous and irreverent Industrial Workers of the World graffiti that the Wobblies scrawled on the inside of the Wabash boxcars.

In 1931, at the age of 32, Conroy teamed up with Ralph Cheyney to found the Rebel Poets organization, a loose affiliation of radical writers who were communicating through correspondence and organized around a set of chapters spread across the United States (as well as in England, Germany, France, and Japan). Conroy hoped the Rebel Poet chapters would be similar to the John Reed Clubs, run by the American Communist Party. The idea was not just one big union—uniting anarchists, liberals, communists, Christian Socialists, Wobblies, populists, and even the godson of J.P. Morgan—but also one big artists’ community. Rebel Poets is now long forgotten, but its members included the poet Louis Ginsberg (whose work was overshadowed by his son Allen’s); Harry Crosby, the editor of Black Sun Press; and notable authors like Sherwood Anderson and Langston Hughes.

Together, printing on an old crank press in a barn in Nebraska, Conroy and Cheyney began to put out a magazine as well as various anthologies. Over the course of two years, they published 17 editions of The Rebel Poet—which was a simple magazine printed on low-quality paper in bold print—as well as three editions of Unrest: The Rebel Poets Anthology. Illustrations in The Rebel Poet depicted capitalists in top hats carrying money bags; there were drawings of heroic and muscular workers earning their wage, as well as portraits of Lenin and Gorky. The work of farmer-poet H.H. Lewis represents some of the best verse of the American proletarian movement, but The Rebel Poet also published didactic schlock like “Karl Marx Started It,” which begins, “All hail to Marx, the champion of mankind!”

Conroy was not above agit-prop, but he was also a committed artist who wanted to develop a proletarian literature that would raise class consciousness. It was a trend that was on the rise. In the early 1930s, with the appearance of New Masses—a publication edited by the irascible Mike Gold, and with contributors that included William Carlos Williams, Theodore Dreiser, John Dos Passos, Upton Sinclair, Ralph Ellison, and Dorothy Day—Conroy found a link to a strong Marxist literary institution in New York. New Masses became a stepping stone for Midwestern writers to reach the Union Square coffeehouses: Conroy became a contributor and recommended his fellow Rebel Poets—drafting from the hinterland in the aesthetic war against Ezra Pound’s occult modernism. “You may yet return triumphantly, Ezra, to a Fascist America,” Gold wrote, “and lead a squad that will mystically, rhetorically but effectively bump off your old friends, the artists and writers of the New Masses. Always ready, but hoping to see you in hell first.”

Pound became more and more aligned with fascism in Europe, but high modernism itself was a threat. Proletarian writers saw it as a bourgeois form that made art too difficult for the everyday person. Rebel Poet Ruth Lechlitner observed that modernists like Gertrude Stein, James Joyce, Marcel Proust, and Jean Cocteau “may be known to a few students of language; but the small-time gangster, or the factory worker…may do more to vitalize a language than any dozen big-time cultish ‘experimental’ writers…. The ‘revolution of the word’ would undermine their purpose, which was the revolution of the world.”

Conroy was a pragmatist: His focus was on regular people. He claimed the sight of Das Kapital on a shelf was enough to give him a headache, and he warned of the alienating danger of the “lower case” and “expatriate” journals publishing writers who had left America for Paris. The high modernists produced complicated experimental work, developing a form that only the intellectual connoisseur could keep up with. “Eccentricity is not an inevitable corollary of merit,” Conroy wrote. “Fidelity to life is always the final and only trustworthy touchstone.” Balzac, Swinburne, and Shelley developed the poetics that Conroy embraced, and his stories concerned such things as the burden of pregnancy for the poor, the starving conditions of wage labor, and the itinerant global working class rapidly developing in the Great Depression.

In 1932, Conroy lost control of The Rebel Poet to a New York faction of party-oriented Communists that he called the “COR-R-R-ECT boys,” who insisted they knew exactly what proletarian literature should be and kept abreast of changing Soviet literary policy. In response, Conroy began The Anvil, an editorially independent quarterly with a Whitmanesque faith in poets as a social force.

As the Depression worsened in the 1930s, journalists went looking for stories in the hinterlands. They sought “a man with a hoe, a country rube who penned verse, a Shakespeare in overalls,” as Mike Gold sardonically put it. Conroy insisted that these journalists needed to look no further: The man with the hoe, the country rube who penned verse, the Shakespeare in overalls—all these and many more wrote for The Anvil.

Within three years, The Anvil reached a circulation of 5,000—or 3,000 more than the Partisan Review. Richard Wright picked up The Anvil in the University of Chicago library and soon published poems in the magazine, including “Strength” and “Child of the Dead and Forgotten Gods.” Conroy published the early writings of Nelson Algren, Meridel Le Sueur, and Yiddish poet Moishe Nadir alongside towering left-literary figures like Maxim Gorky and Langston Hughes. Leon McCauley, who taught himself to write in prison, was one of several Wobblies contributing to The Anvil, and the magazine began to develop its own politics. With its IWW and anarchist streak, The Anvil deviated from the New York–based Communist Party and Soviet orthodoxy.

In 1935, with Conroy busy on a second novel and the economics of publishing shifting, The Anvil fell on hard financial times while retaining a valuable mailing list. The magazine was officially brought to New York via a merger and came with a new title: Partisan Review and Anvil. That entity subsequently split from the Communist Party’s distribution support in 1937 after the Soviet-Nazi alliance, and the Partisan Review relaunched. In the process, The Anvil’s name died.

Conroy set out to be a writer as well as an editor. He began his first novel, The Disinherited, in the late 1920s, and when it was published in 1933, it became the standard-bearer for the proletarian novel: a bildungsroman about a boy named Larry Donovan growing up in a coal-mining camp, seeking factory work in St. Louis and then Detroit, joining the itinerant, unemployed masses, and laboring on a road crew—anything to survive the Great Depression’s hard winters.

Yet make no mistake: Conroy was not interested in gloomy tales of a dehumanized subproletariat. Humor, as well as a reverence for nature and naturalism, Midwestern myth, and expressions of worker dignity, all combine to give Conroy’s stories a life-affirming quality similar to traditional forms of folk art. In the end, human resourcefulness and endurance prevail, and there’s nothing better than a joke about the boss.

Both The Disinherited and Conroy’s later novel, A World to Win, feature a cast of characters that include people of all faiths, genders, and races, and both culminate in their protagonists’ reaching epiphanic moments of revolutionary fervor. Working on a highway paving crew in the middle of farmland, The Disinherited’s Larry Donovan has borne witness to years of immiseration—of his friends, his family, and thousands of strangers. Under the hot sun, a Black man has worked himself to death. News from the city arrives: Some 15,000 people have marched on the St. Louis mayor’s office. The disenfranchised are demanding to be fed. The St. Louis police have thrown tear-gas bombs into the crowd, but “the workers stood their ground,” a labor organizer tells Donovan.

The “July Riot” in The Disinherited is based on a real event. The organizer tells Donovan that a Black worker in St. Louis was “burned to the shoulder but he kept catching the bombs and hurling them back” at the police. This defiance is enough to convince Donovan that the individual cannot win alone and that his voice is needed in the class war: “I knew that the only way for me to rise to something approximating the grandiose ambitions of my youth would be to rise with my class, with the disinherited.”

Popular

“swipe left below to view more authors”Swipe →

In A World to Win, published in 1935, Conroy splits himself in two as Leo and Robert Hurley, brothers who represent Conroy the worker and Conroy the intellectual. Leo builds a wall of “defensive dignity and a sense of importance” as a laborer who sees men’s fingers taken by the sawmill, while Robert aspires to the writing life. He attends the University of Missouri in Columbia and scrapes together white-collar work that he balances with art. Both novels are unique in their blend of Midwestern folklore, worker narratives, true tales, humor, and vulgarisms, and both center their revolutionary epiphanies on the 1932 July Riot. In the end, Leo and Robert find themselves in St. Louis with nothing to lose. Leo has murdered a policeman, and the local fascists—America First vigilantes—want a brawl with the Hurley brothers and all their communist friends.

In 2014, a St. Louis resident named Edward Crawford was photographed throwing a flaming tear-gas canister back at police during the Michael Brown protests. Crawford reported that he had just come from work in a kitchen and was dressed in an American flag shirt. In the photo, he is hurling a flaming, smoking grenade back at the militarized police in Ferguson. The image became emblematic of justice-seeking defiance in the face of an overwhelming, antagonized police state. It is a natural echo of the last century of racist, violent American capitalism, and while the 1932 July Riot is largely forgotten, it is preserved in Conroy’s art because his life was devoted to telling the stories of working people, up against all odds, hurling rocks at Goliath.

By 1937, Conroy’s literary fortunes were shot, but a Guggenheim grant helped him maintain his research and writing. Conroy moved to St. Louis, where union organizing was on the rise—the victory of Black women workers in the Funsten Nut Strike had sent a shock of energy through labor organizing.

In the crummy East St. Louis taverns, Conroy drank heavily, wrote satires, and became a ringleader of the “Fallonites”—a group of pro-labor toughs who would enter bars chanting for the Congress of Industrial Organizations: “CIO, CIO, CIO.” The Fallonites were a threat to regular bar-goers, but they were also theatrical, gravitating to Conroy with their own artistic ambitions. The group would get into brawls, sing bawdy lyrics to the barroom, and put on the occasional piece of Satanic theater, an infamous “black mass.”

In 1940, as McCarthyism ratcheted up, Conroy moved to Chicago, where his satires were used to raise funds to start The New Anvil. The magazine enjoyed a brief run publishing writers like William Carlos Williams before it ceased within the year. Conroy was hired on to the Illinois WPA (IWPA) Project, working closely with the Harlem Renaissance poet Arna Botemps. The two completed an IWPA study of Black migration, which attracted the interest of the FBI. Agents interviewed Conroy and Bontemps about the Nation of Islam, which the FBI had connected to the subversive Japanese Black Dragon Society. Conroy and Botemps both denied any such links. It was another paranoid delusion of the early Cold War. “The only safe thing to do is curse Moscow,” Conroy wrote in a letter to a friend, “and if you do that many of your past sins are shriven.”

After the IWPA lost funding, Conroy found employment with Nelson Algren in the Venereal Disease Control unit (or “Syph Patrol,” as they called it), located in the Chicago Health Department. A WPA spin-off organization, the VD Control sent Conroy as an “investigator” to taverns and suspected bordellos to deliver summonses. He would escort prostitutes to health clinics for tests, and, at least once, he was threatened by a pimp wielding a knife.

Finally, the Sage of Moberly got a steady (yet monotonous) job editing encyclopedias in Chicago. It was the steady white-collar employment Conroy wanted for all writers. But still, FBI agents showed up again. His employer turned the agents away, telling them, “He’s a good editor, and I don’t care about his political ideas.”

Conroy’s novels did not attract interest again until the late 1960s, after some of the Red Scare receded. With Arna Botemps, Conroy published the Illinois Writers Project study of migrating Black populations in 1966, which was reprinted as Anyplace but Here. In 1967, Gwendolyn Brooks presented Conroy with the first Literary Times Prize, citing “his aid and encouragement to young writers and his overall contributions to American literature, particularly his novel, The Disinherited.” Conroy moved back to Moberly and won an honorary doctorate from the University of Missouri, the Mark Twain Award from the Society for the Study of Midwestern Literature, and a National Endowment for the Humanities artist grant. In 1985, he published The Weed King and Other Stories, and spent his final years offering wisdom to traveling scholars and readers who made the pilgrimage out to Missouri to visit the Sage.

Jack Conroy passed away in 1990. He was buried in Moberly, in the Sugar Creek graveyard alongside his two brothers and his father. One brother was killed coming home at night from work at the Wabash Railroad shops. He was 14. Conroy’s father was killed “firing shots”—setting off blasting caps in the Monkey Nest coal mine. “Monkey Nest’s mouth is stopped with dust,” Conroy wrote in The Disinherited, “but in its time it had its pound of flesh. Yes, I figure it had its tons of flesh, all told, if laid side by side in Sugar Creek graveyard.”

Conroy’s fiction is a significant body of work artistically and historically, though almost none of his books are still in print. Less tangible is his role as editor and champion of untried literary voices that went on to have a profound effect on American letters. “Conroy planted his Anvil in Missouri soil,” writes Douglas Wixson, Conroy’s literary executor. “It spread its connection horizontally throughout the cartography of American social experience.”

While complicated modernist works like As I Lay Dying and The Waste Land became canonized, Conroy and his comrades, in their proletarian literature, told stories of working people realizing solidarity. These writers and their works enjoyed a few brief years of Depression-era popularity, which was eventually overshadowed by America’s postwar prosperity and decades of Cold War red panic. But Jack Conroy wholeheartedly believed that the American proletariat could (and would) awaken to its destiny as the democratic vanguard. First, the “weeds” of society needed to hear the story of their power in their own language—to see themselves and the stories of their lives depicted in art.

Thank you for reading The Nation!

We hope you enjoyed the story you just read. It’s just one of many examples of incisive, deeply-reported journalism we publish—journalism that shifts the needle on important issues, uncovers malfeasance and corruption, and uplifts voices and perspectives that often go unheard in mainstream media. For nearly 160 years, The Nation has spoken truth to power and shone a light on issues that would otherwise be swept under the rug.

In a critical election year as well as a time of media austerity, independent journalism needs your continued support. The best way to do this is with a recurring donation. This month, we are asking readers like you who value truth and democracy to step up and support The Nation with a monthly contribution. We call these monthly donors Sustainers, a small but mighty group of supporters who ensure our team of writers, editors, and fact-checkers have the resources they need to report on breaking news, investigative feature stories that often take weeks or months to report, and much more.

There’s a lot to talk about in the coming months, from the presidential election and Supreme Court battles to the fight for bodily autonomy. We’ll cover all these issues and more, but this is only made possible with support from sustaining donors. Donate today—any amount you can spare each month is appreciated, even just the price of a cup of coffee.

The Nation does not bow to the interests of a corporate owner or advertisers—we answer only to readers like you who make our work possible. Set up a recurring donation today and ensure we can continue to hold the powerful accountable.

Thank you for your generosity.

More from The Nation